Abstract

Background: Frontline clinical trials in DLBCL can exclude up to 24% of the real-world population based on 5 lab-based eligibility criteria (Khurana et al. JCO 2021). Furthermore, these patients have worse clinical outcomes and increased deaths due to lymphoma progression suggesting, that the patients that could benefit the most from novel therapies in clinical trials are left behind. However, the details of chemotherapy dose intensity and its contribution to poor outcomes remain unknown. We sought to evaluate the chemotherapy dose intensity and reasons for dose alterations in these clinical trial ineligible patients and to identify a subset of these patients that can potentially be rescued back into the trials.

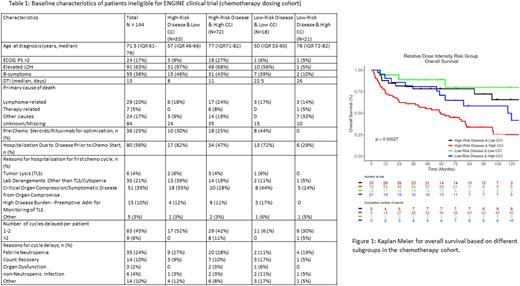

Methods: Patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma were enrolled from 2002 to 2015 in the Molecular Epidemiology Resource (MER) of the University of Iowa and Mayo Clinic Lymphoma SPORE and prospectively followed. Clinical data, treatment, and outcomes were abstracted from medical records using a standard protocol. Eligible patients had DLBCL, initiated frontline immunochemotherapy (IC), and were ineligible for the ENGINE trial (an ongoing phase III multicenter trial - most restrictive per our prior analysis) based on ENGINE trial's lab criteria. Average relative dose intensity (ADI) was calculated for doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide based on both the actual dose and time to deliver the doses (Bataillard et al. Blood Advances 2021). To identify patients that could be rescued back into trials we divided the patients into 4 categories (Table 1) based on disease risk and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). High-risk disease was defined as IPI >2 and/or diagnosis to treatment interval (DTI) < 14 days; high-risk comorbidity score was CCI > 2. Baseline patient characteristics and chemotherapy details including reasons for dose alterations were compared between groups.

Results: Of the 1265 IC treated DLBCL patients in MER, 305 (24%) patients were deemed ineligible for the ENGINE trial based on 5 lab criteria. Ineligible patients were significantly older (median 68 vs. 61 yrs), with worse performance status (PS >2, 29.8 vs. 12.6%), had elevated LDH (70 vs 52%), high-risk IPI (57 vs. 32%), shorter DTI (median 13 vs. 16 days), and more B-symptoms (43 vs 23%). Of the 305, 144 (47%) patients were treated at Mayo and had complete details on chemo dosing. The baseline characteristics of this cohort and different subgroups are shown in table 1. Over 95% of patients were planned for 6 or more chemo cycles but only 73% completed planned cycles. 56% of patients were admitted to the hospital for cycle 1. The most common reasons for inpatient chemo delivery were symptomatic disease (35%), and lab derangements other than tumor lysis or cytopenia requiring intervention (21%). 19% (28/144) of patients had planned reduction in cycle 1 for both doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide with the most common reasons of older age and comorbidities (57%). Hospitalization/ER visits occurred in 38% (55/144) of the patients after cycle 1, with 22% (32/144) febrile neutropenia. 51% of patients had 1 or more chemo cycles delayed with the most common reason of febrile neutropenia (24%), followed by count recovery (10%).

The median age was greater for patients with high CCI compared to low CCI for both high risk (77 vs 57) and low risk (78 vs. 50) disease groups. Patients with high-risk disease more commonly required inpatient admission for cycle 1 and pre-chemo steroids and rituximab optimization. All patients maintained >60% ADI in the low CCI groups (range 60-100%) compared to high CCI (range 20-100%). Clinical outcomes (overall survival) in the high-risk disease and low CCI group were significantly better than high-risk disease and high CCI (Figure 1).

Conclusions: Patients who were ineligible for clinical trials based on lab-based criteria had disproportionately more high-risk disease features. Patients with high-risk disease more commonly required pre-chemo steroids and rituximab optimization. While small numbers and unbalanced subgroups limit interpretation, low CCI patients despite high- risk disease were able to maintain ADI and attempts should be made to include these patients in clinical trials. High CCI and high-risk disease subgroup had the worst outcomes and most dose alterations suggesting an unmet need with alternative less toxic treatment strategies and comorbidity management.

Disclosures

Ansell:SeaGen: Research Funding; Takeda: Research Funding; Bristol Myers Squibb: Research Funding; Regeneron: Research Funding; Affimed: Research Funding; Pfizer: Research Funding; ADC Therapeutics: Research Funding. Cerhan:BMS/Celgene: Research Funding; Genentech: Research Funding; GenMab: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; NanoString: Research Funding; Protagonist: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Nowakowski:Bantam Pharmaceutical: Consultancy; Blueprint Medicines Corporation: Consultancy; Celgene Corporation/Bristol Myers Squibb: Consultancy, Research Funding; Curis, Inc.: Consultancy; Daiichi Sankyo Inc: Consultancy; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd: Consultancy, Research Funding; Genentech, Inc: Consultancy, Research Funding; Incyte: Consultancy; Karyopharm: Consultancy; Kite Pharma Inc.: Consultancy; Kymera Therapeutics: Consultancy; MorphoSys US Inc: Consultancy; NanoString: Research Funding; Ryvu Therapeutics: Consultancy; Selvita: Consultancy; TG Therapeutics: Consultancy; Zai Lab: Consultancy. Witzig:Karyopharm: Other: Clinical Trail Support; ADC Therapeutics: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Curio Science: Honoraria; Kura Oncology: Other: Clinical Trail Support. Maurer:Adaptive Biotechnologies: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; BMS: Research Funding; GenMab: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Morphosys: Research Funding; Roche/Genentech: Research Funding.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal